Frottages, first series2003

Doing what needs to be done.

Ciguri, Anna, and Antonin I recognize what I please and not what I am told to.

Antonin Artaud

Mexico. In late August 1936 the Mexican minister of education arranged for Antonin Artaud to ... more

Frottages, first series2003

Doing what needs to be done.

Ciguri, Anna, and Antonin

I recognize what I please and not what I am told to.

Antonin Artaud

Mexico. In late August 1936 the Mexican minister of education arranged for Antonin Artaud to visit the Sierra Madre Occidental, where “Mexico’s red soil still speaks its authentic language”. After a long waiting period, Artaud traveled to the region inhabited by the Tarahumara Indians. A tribe still living in the Stone Age, like dead people, commented Artaud, but famed for its tenacity and courage, a fact to which their name also refers (it has the meaning of “runner”). It was only after a long and tedious ride across high mountains that he arrived at his destination. This journey was real torture, exacerbated by withdrawal symptoms caused by the absence of heroine, and he likened it to his own crucifixion endured under excruciating pain, chained to his horse like a machine, accompanied only by his guide/interpreter. (Eleven years later, however, he described this journey as an “enchantment”.) The atmosphere is nightmarish and the landscape anamorphotic—everything is a sign or bears a sign, everything has a meaning.

Nighttime. Deadly silence, a small coastal town in North America, not far from Mexico City, where the “Square of Three Cultures” is inaugurated. There is only an ominous, cautious crowing of black birds, presaging, like the eye of the storm, the impending havoc wreaked by these creatures. And yet nothing is in fact happening; in real space all that counts is the eye of the contemplative viewer sitting in a movie theater row. In 1963 Hitchcock directed “The Birds”, and his compatriot Edwin H. Land designed the first instant (Polaroid) camera for color pictures. In Berlin, despite Kennedy’s visit (and his assassination three months later), “the big night was ruined”, which Henry de Montherlant also noticed: “Le chaos et la nuit”—Antonin had already roamed the realm of darkness for fifteen years—and in Belp near Berne Anna was born.

Ciguri. His life had the sparkle of magic. The Tarahumaras performed the old Peyotl rite. The mescaline obtained from the Peyotl cactus (Iophophora williamsi) is a hallucinogenic substance which heightens sensitivity, especially visual perception. Inebriation involving intense colors is also frequent, but also an identification with the plant itself—a plant awareness of sorts is created. At first he was denied it, the long and tormenting period of withdrawal, but then he joined Ciguri’s rite of creation. Ciguri was a man, a man born from within himself, as it were, he designed himself in space when God killed him.

Dark red. When (very) young human beings start to comprehend the world surrounding them, they take whatever they can get hold of into their mouth, “sucking on the world”, so to speak. What is essential is a haptic differentiation of tastes, i.e. the olfactory evidence produced by the mouth as an organ, from the tactile relationship between fingers and hand. But there is also a fair amount of feeling, probing, groping, holding, and guiding. Somewhat later in the social cognitive process words, notions, and sounds are learned and allocated to specific objects based on convention. Things get really intriguing, though, when certain synaesthetic phenomena emerge—colors, for example, generate specific sounds or tastes, names conjure up colors, and sounds become visual. This does not occur all that rarely, and is sometimes—and erroneously—diagnosed as a perceptive disorder. However, this state may be artificially induced by means of hallucinogenic drugs such as LSD or mescaline.

Namur. Henri Michaux called his works on paper, created from the mid-fifties almost “automatically”, under the influence of hallucinogens, “mescaline drawings”. These disintegration processes of visual forms, recorded on paper by means of ink, are marked by a rhythmic structure and near-graphic precision which allow informal and abstract “writings” about the world to correspond to something scribbled in which colors and sounds are inscribed. And yet nothing is tangible, nothing is really definite, and a shapeless shape only provides syntactic evidence of a semantic layer positioned beyond virtual awareness. Michaux writes the following about his experiences with mescaline: “Where there used to be a surface, the ground, you now have hundreds or even thousands of dots in front of you that you are all able to perceive individually, each in its own characteristics.” In a different context, when referring to the adventurer of lines, Paul Klee, he said: “I arrived at the purely musical, the real still-life.”

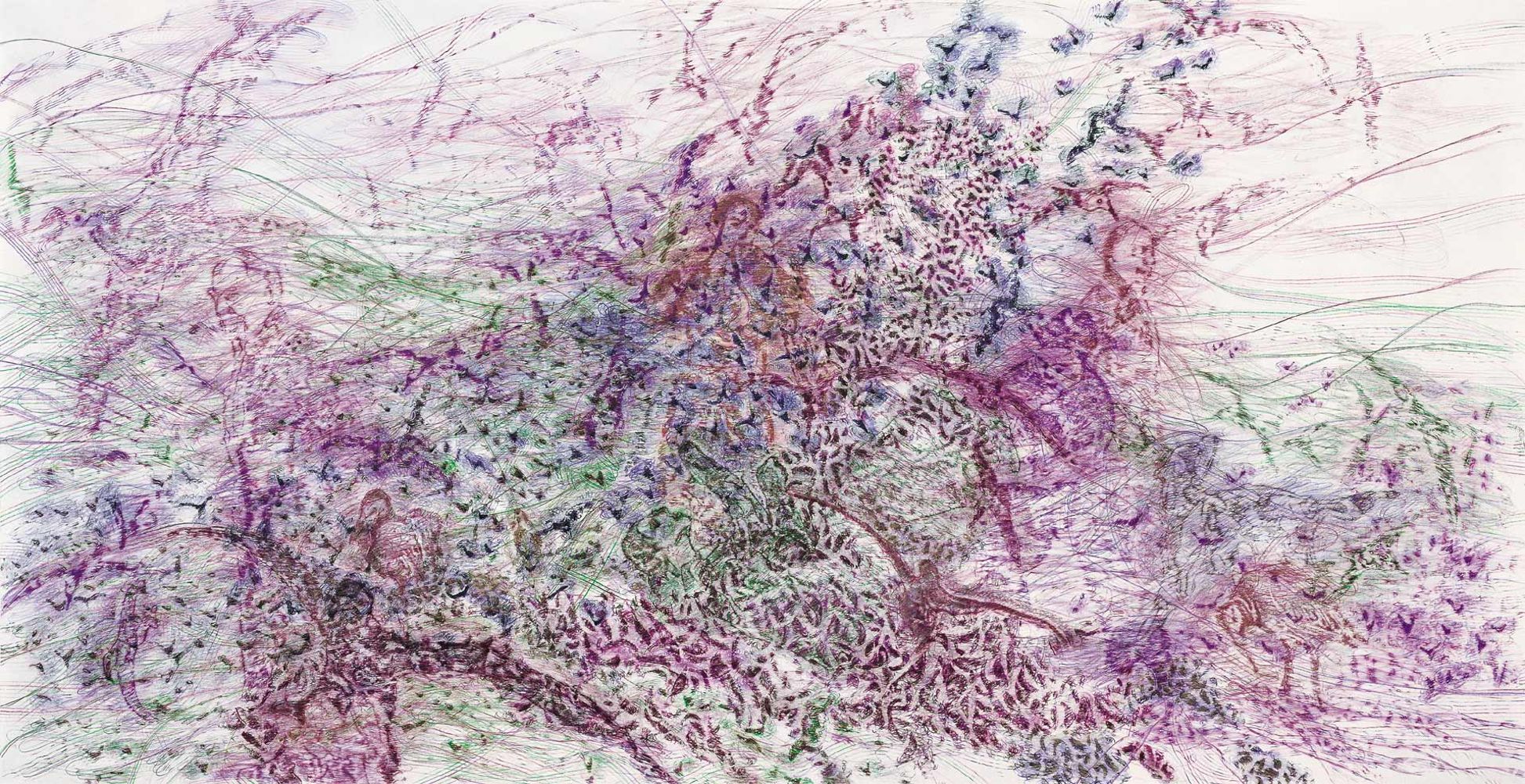

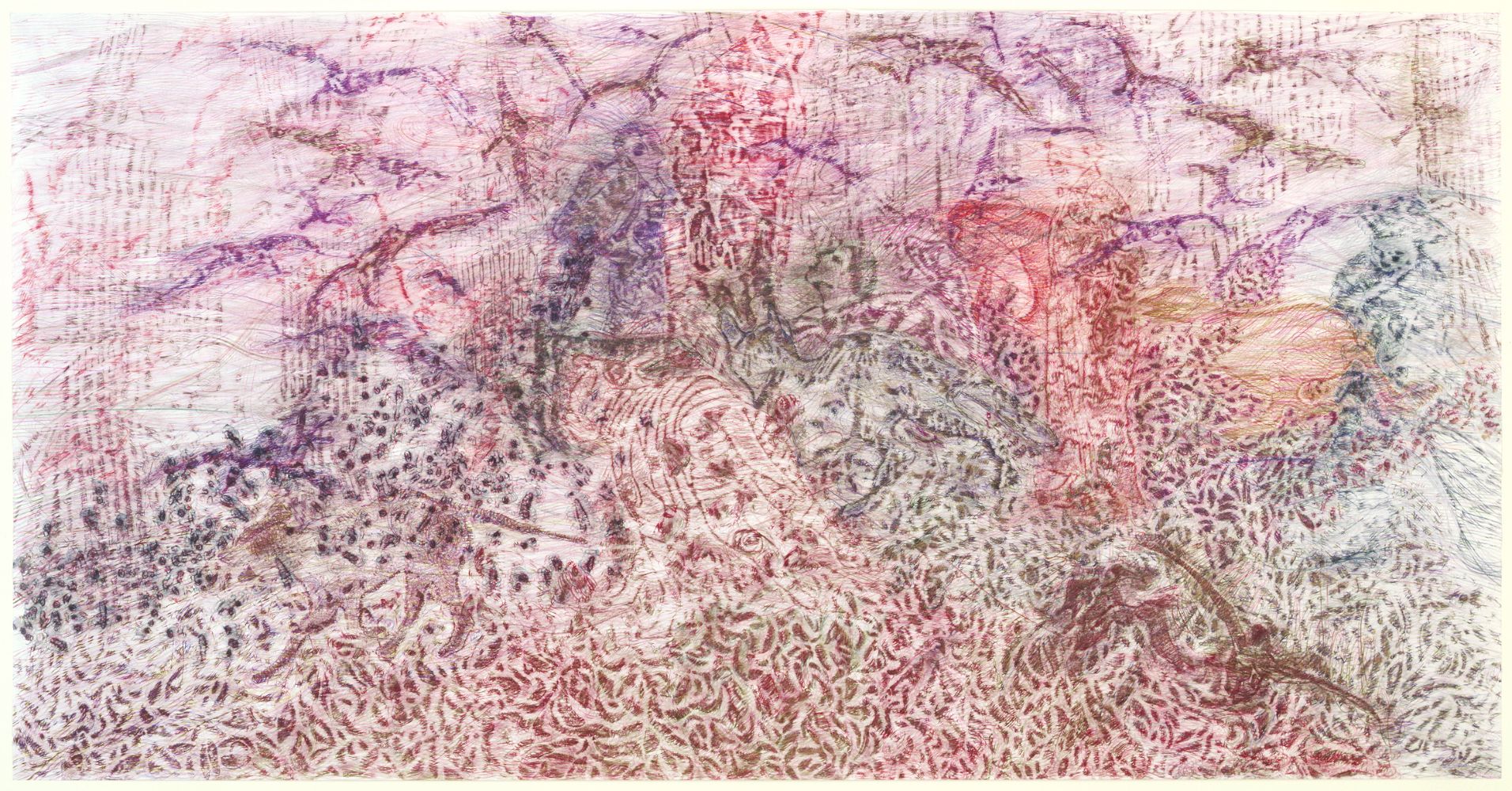

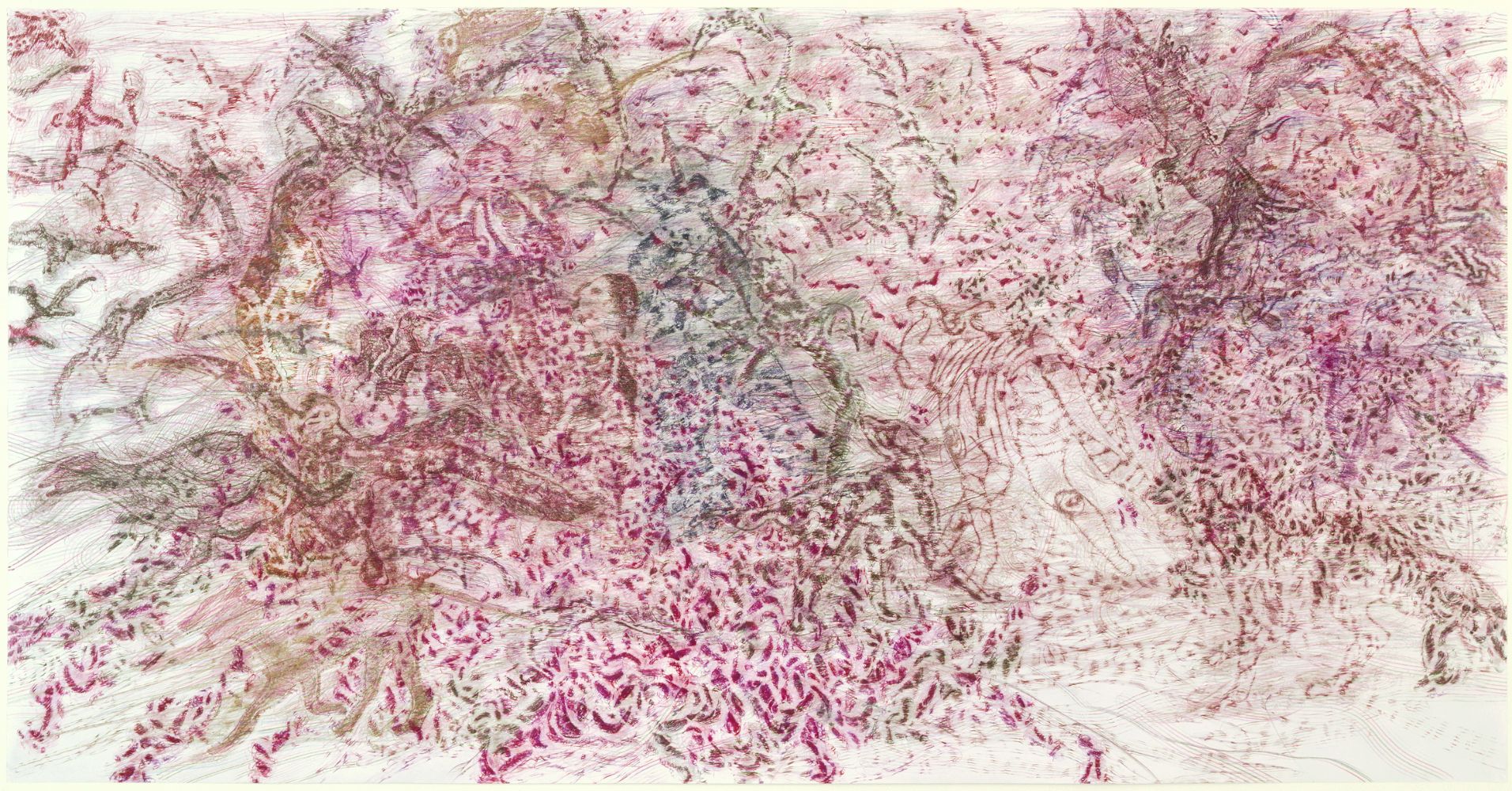

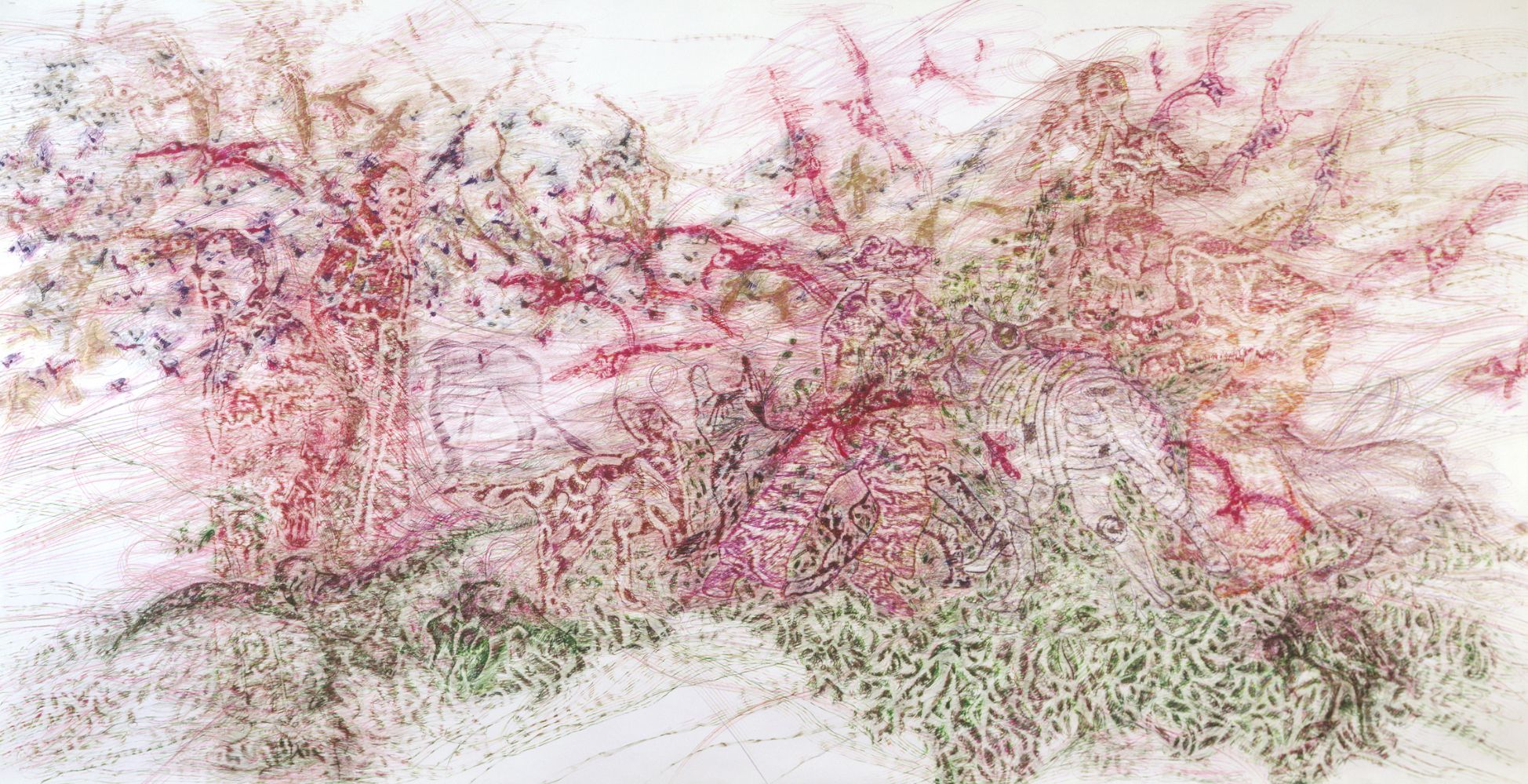

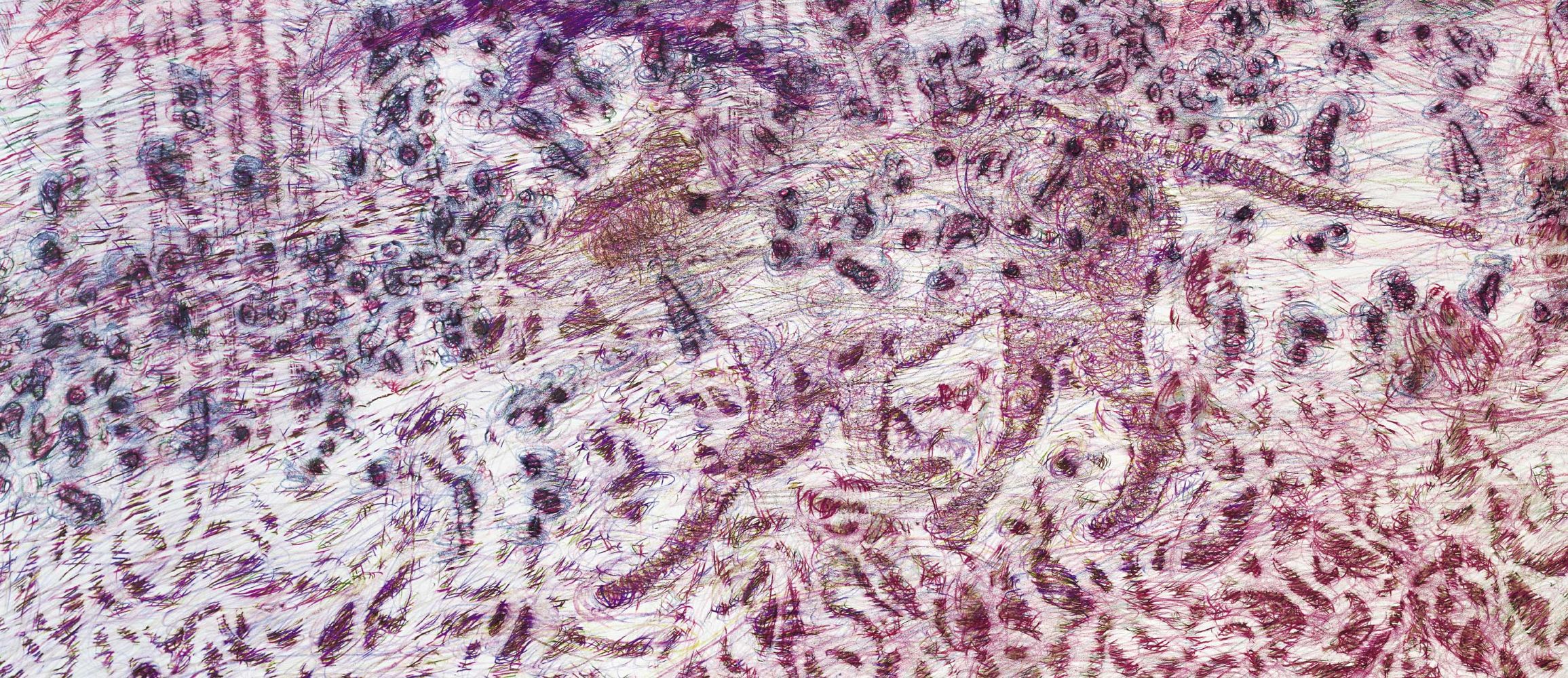

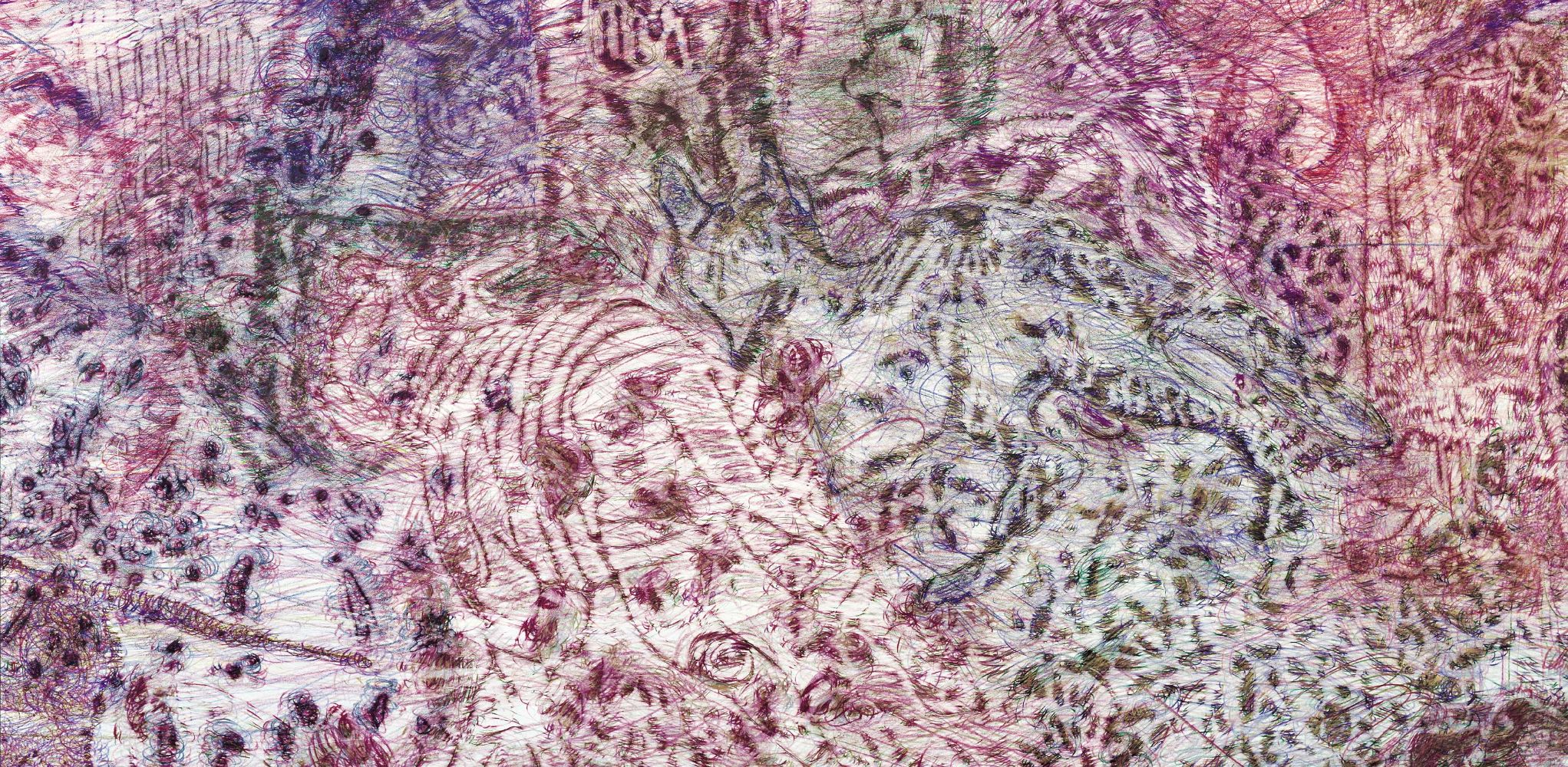

Lines. Lines and points keep us in space. Fixed or vanishing points, grids, pixels, coordinates, positions, references. In between lines, straight lines, routes, vectors, the relation between points, curvatures, angular ratios. The art of Anna Amadio is characterized by an interaction between two-dimensional points, or, to be more precise, one-dimensional points, and other points as well as the two-dimensional relation between lines which is quickly invested with aspects of three-dimensionality. She invariably devises landscapes, in the way a planner would, but she does not really approach them functionally, i.e. by asking the question of how to create land, and for what purpose. Still, land is taken seriously in its relation, as a definable category, and perceived as an issue involving space between points and lines. In her new drawings perspectives are suggested, toyed around with, and distorted.

Opiates. What is unusual and quite remarkable is that her paper works, just like her big, transparent, and inflatable objects, exude an impermeability and a certain uncanny quality, for all their intended lightness and single-layered internal life. This may be due to the fragility, nervousness, or graphic restlessness of her points and lines which, when looked at closely, engender a kind of interference of parallelism, a field of force acting from within. Abstract productivity—and a commitment to life—are given a specific form. Determining the origin or sequence of layers reliably is impossible in her drawings. Concentrations, however, can be located, and the same goes for centers of force in which variety and redundancy have a substantial and sometimes hallucinogenic effect on the viewer. Occasionally curvatures complement each other and form an image of a tree or a forest, an animal or a human being obtained only by the viewer’s gaze. Here the formal similarity to Michaux’s mescaline drawings and depictions of a non-representational world replete with quasi-objects is striking, and they are not less compelling, in terms of their linguistic analogy, than Artaud’s jungle visions in which the dead (the Tarahumaras) exist in a fertile land of red soil, hovering like shadows, a mere noyée d’ombre.

Still-lifes. While in Anna Amadio’s drawings graphic oscillation is recorded on paper like bundles or lines of parallel traces of organic, biological, or physical structures and textures, she resorts to the experiences gained with surfaces in her inflatable objects, even though the origin of her artistic endeavors lies in objects. Flickering graphics, buzzing hatches, and nervous fields of force converge in a space of light and air and blend into a cocoon in transparent polyethylene cushions and PVC sheets, a cocoon whose emergence and presence are taken for granted. They are simply there and that is their raison d’être. They are constructive, pretend functionality, while really their function and origin (a tattoo or a nomadic tent) are not easily recognizable. At the same time they are invariably monumental, and exceed our spatial comprehension, our comprehension of that space on which—rather than for which—they have been specifically modeled. “Anatomy of an attack” was the name Anna Amadio once chose for a big inflatable object which, spanning air and light in space, articulated the imaginary tectonics of ephemeral being. Also a full-fledged still-life. That is precisely what connects us to them. A presence in space which appears to us deliberate, functional, and hence just about right, familiar and yet transitory, unknown, full of yearning, a longing felt against the passage of time. It is always a mystery. Doing without words. A spiritual still-life.

Schrödinger’s cat. In Anna Amadio’s most recent works the original image is a raised contour or one scratched into a soft mass of glue which, by being vigorously rubbed with a set of six to nine pens, leaves an image on paper. This rubbing technique employed by Surrealists is derived from experiments concerning the unconscious, from écriture automatique, where the emerging image is an objective copy of the model. And yet gestures invariably impact the appearance and thus the effect of an image. The magic of imagery. Is it dead or alive, that was the question of cognitive theory raised by Werner Schrödinger’s experiment with the poor cat exposed in a closed box to deadly radioactivity. But we need to look inside the box to answer this question. Just like in Amadio’s case. We must associate, query, ignore, and affirm, like malleable wax tablets on which, as was already stated by Plato, our memory writes things we perceive and overwrites them permanently, but without completely erasing older impressions. This frottage of our mind is the “theater of cruelty” (Artaud) in the real, symbolic, hallucinogenic, and imaginary confrontation of necessity. What is meant here is not media imagery but images affecting our souls, vibrating and resonating the wax tablets of the real world as spiritual still-lifes and shadow-like signs. This enlightening frenzy of Artaud and Michaux—there are some who search for Ciguri in vain—is right in front of us, in the shape of a double. Pleasant shivers running down our spine. Like the flickering lines in Amadio’s sheets and magical inflatable objects, grand tracings of borders of reality in the lovely pestilence of imagination. Do we let the cat live? Photos are nowadays taken and processed digitally. And in the box it is dark, but outside birds are lurking. Well, the cat couldn’t care less.

Text Gregor Jansen

Frottage 50c |2003 |Frottage, Farbstift auf Papier |150 x 295 cm [H W D]

Frottage, Detail |2003 |Frottage, Farbstift auf Papier

Frottage 50b |2003 |Frottage, Farbstift auf Papier |150 x 295 cm [H W D]

Frottage 50d |2003 |Frottage, Farbstift auf Papier |150 x 295 cm [H W D]

Frottage, Detail |2003 |Frottage, Farbstift auf Papier

Frottage 50e |2003 |Frottage, Farbstift auf Papier |150 x 295 cm [H W D]

Frottage, Detail |2003 |Frottage, Farbstift auf Papier

Frottage 50a |2003 |Frottage, Farbstift auf Papier |150 x 295 cm [H W D]

Frottage, Detail |2003 |Frottage, Farbstift auf Papier